19 Nov Can more role models for girls now resolve the gender leadership gap in the future?

Senior Lecturer in Culture, Media, and Education

The way to resolve the gender leadership gap, according to popular wisdom, is to provide girls with more role models. The ‘if she can see it she can be it’ argument proposes that exposure to women in decision making positions in traditionally male-dominated fields will encourage girls to aspire to such positions themselves.

This idea has been taken up by many of the girl-empowerment initiatives that proliferate across the internet: For example Sheryl Sandberg created her ‘Ban Bossy’ campaign as the younger sister of Lean In, using celebrity women leaders to exhort girls to develop their leadership potential ; Edwina Dunnhas received an OBE for her ‘The Female Lead’ initiative, collecting profiles of ‘inspirational female role models’ to offer to school via books and online; Geena Davies (she of Thelma and Louise fame) has founded an Institute on Gender in Media, with the purpose of influencing media industries to create more, and better, representations of girls and women in entertainment targeting children.

This is an important issue: representation is an important marker of equality, and many children grow up in media-saturated environments that help shape their ideas about the world and their place in it. But the gender leadership gap is tenacious, and the ways in which young people engage with media figures are complex and varied. The assumption that inspiration will lead to imitation can depend on simple gender-matching that ignores other, limiting cultural and socio-economic factors.

With my Oxford Brookes colleague and co-researcher Hannah Yelin, I have just completed a pilot study for a project, ‘Girls, Leadership and Women in the Public Eye’. We have talked to girls in a range of state schools across England, asking them about the women they admire, about their ideas of good leadership, and about their own experiences and ambitions. Our findings suggest that role-model solutions alone are unlikely to deliver their popular promise of resolving the gender leadership gap for three key reasons:

First, girls are acutely aware of the negative experiences of women in the public eye. The concerns that girls raised included the online misogyny directed at women politicians, celebrities and campaigners, especially BAME women. They also described traditional media representing women leaders in demeaning, stereotyped ways, and as judging women more harshly than their male counterparts. So, increased representation is not in itself likely to be effective if that representation is negative.

Second, girls saw women leaders as too often drawn from a small, privileged pool. While our participants admired some of these women, they did not see them as role models. They felt that such women would not be able to understand nor help remove barriers for girls like themselves. For these girls, for a role model to be of the same gender was not enough to make them identify with her.

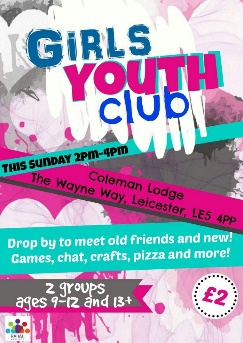

Third, girls have scant experience of meaningful decision-making; the proffering of distant role models via various media cannot compensate for this. For most of the girls in the study, roles of responsibility were limited to their home/domestic lives. If they took part in extra-curricular activities they were likely to have more experience, and girls who participated in out-of-school clubs (especially Girlguiding) reported the most involvement. However, many had seen their youth clubs close or offer a much reduced, volunteer-dependent range of activities. While some school subjects (especially RE) gave them opportunities to practice debate and collaborative decision-making, on the whole they were unlikely to get a taste of leadership.

The implications of these findings are troubling. They suggest that engagement with media representations of women in the public eye acts as a deterrent to girls because of the conditions of women’s visibility. Even where this is not the case, proffered role models are likely to be women who come from positions of advantage, and this means their experiences may not resonate with many girls. Finally, distant role models cannot compensate for a much-reduced youth infrastructure, and nor are many hard-pressed schools able to compensate for this. Girls in our study were interested in the processes of leadership, in different models, and especially in leadership for social justice, but they lacked opportunities to develop such interests.

For the next stage of our project we will be conducting further interviews with girls from groups identified as particularly likely to be under-represented in leadership, and also with girls from elite backgrounds that are proportionately well-represented compared with other women.

An executive summary of the pilot findings is available here. If you would like to know more about the project please contact Michele Paule

No Comments