31 Jan “I wish I were a man”: women on the frontlines in the United States of America in WWII

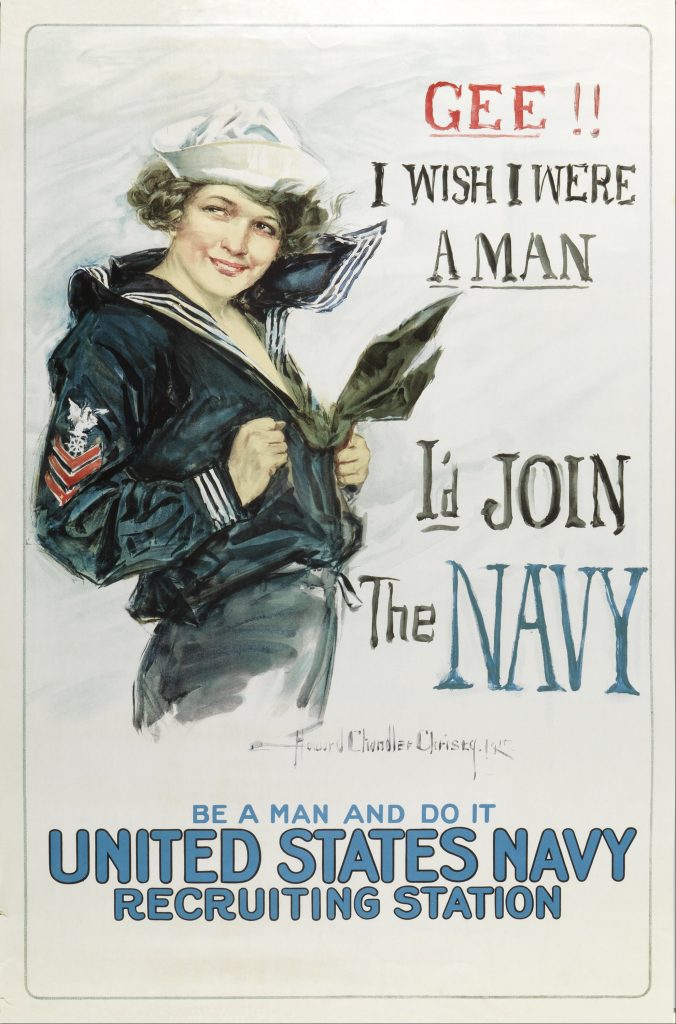

“Be a man and do it” … A smiling young woman in a US Navy uniform encourages men to join the Navy on a World War I recruitment poster. That woman is Bernice Smith (1897-1990). Initially rejected from a conventional Navy position, Bernice became the first woman in California to enlist in the Navy during the Great War. The US Navy approved enlistment by women for administrative posts only in 1917. Bernice would later go on to serve as a clerk in the US Army during World War II (WWII).

Women’s struggles for equal participation in the US received a decisive yet short-lived boost during WWII. After winning the right to vote in 1920, American women fought for equal rights and responsibilities. Labor market access and equal pay were plausible goals, which were obtained in part during WWII.

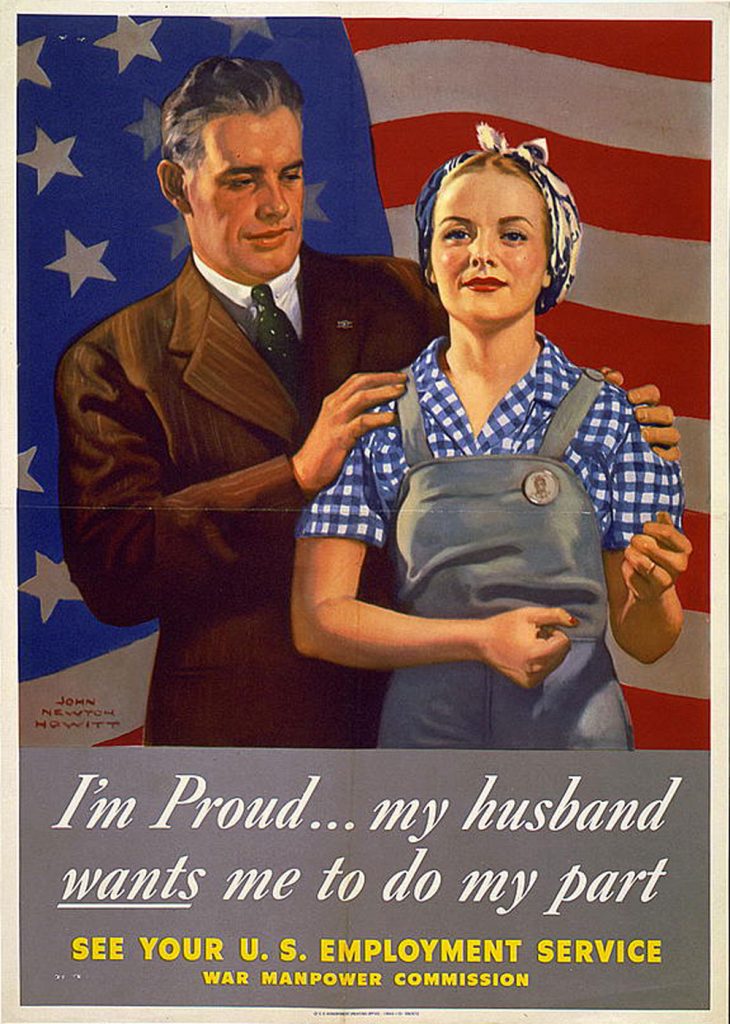

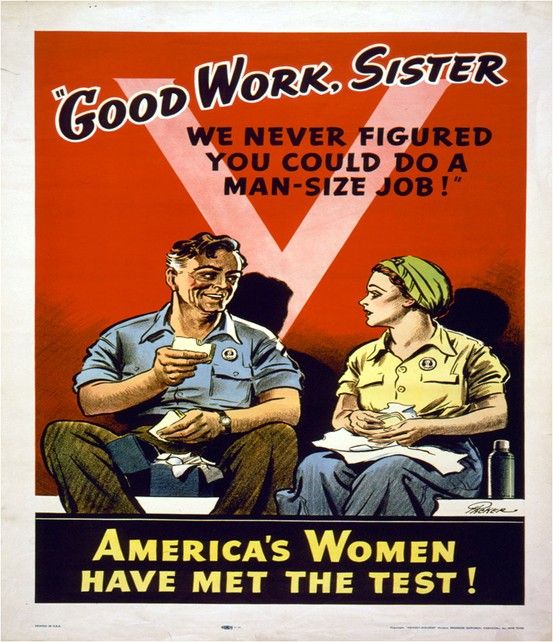

The war enabled women to step outside of the positions which had been conventionally assigned to them: clerical work, cleaning, teaching, nursing, and hospitality. Many women entered the labor market for the first time, finding vacancies in former male-held roles due to the mobilization of large numbers of men for the war effort. The government invested heavily in recruiting women to work on the front lines, both at home and abroad. Propaganda campaigns were in full swing, although they tended to reproduce societal stereotypes and prejudices against women.

The economy during the war desperately needed women’s labor. In a context of heightened patriotism, women proudly took part in all kinds of ‘manly’ jobs, including the fictional character in ‘Rosie the Riveter’. On the home front, women worked as ambulance and public transport drivers or as mechanics in war factories, building ships, airplanes, and weapons. However, they did so in poor, unhealthy and sometimes dangerous conditions. Women were treated differently to their male colleagues, earning far lower wages for the same work and experiencing harassment from some men who opposed their presence in the workplace.

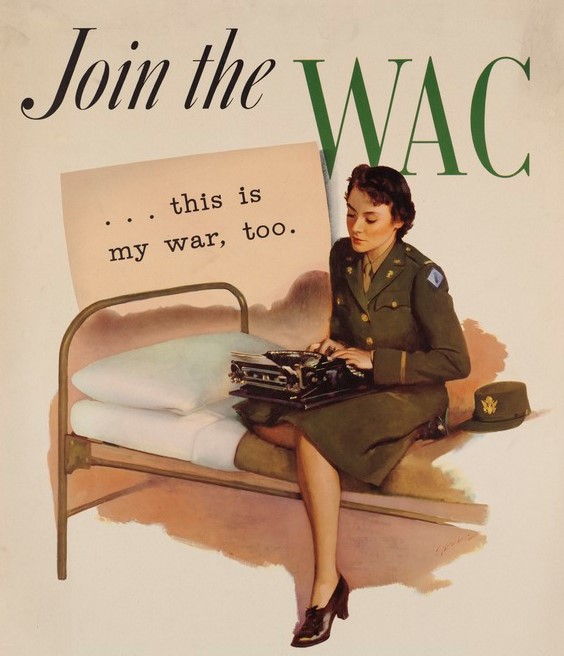

Other women chose to join the armed forces, which represented the undisputed prototype of masculinity. Around 350,000 American women served as volunteers in the auxiliary military corps created ad hoc when the war began and were assigned to different military branches at home and abroad. The goal was to free up soldiers from all non-combatant positions (from administrative jobs to radio operators and airplane pilots) so that they could be sent to the front lines. These new military corps joined the traditional Navy and Army nursing corps, which contained large numbers of women. However, the women in these corps were subject to the same patterns of discrimination and inequality that were present in civil society at the time, which viewed the home as the most appropriate place for them. Female soldiers also had to overcome resistance and disdain from their families, friends, and society in general, as they were considered a threat to men’s status as soldiers.

The US Army was one of the most discriminatory military branches for female soldiers. Until September 1943, the women enlisted in the Women’s Army Corps (WAC), created in May 1942, received lower pay than their male counterparts in the regular Army. It was the first time that women had served in roles other than nursing in the history of the US Army. Whereas women became a permanent part of the US Navy in 1948, it took another three decades for the Army to fully integrate women into its ranks. Around 150,000 women served in the WAC. Over 124,000 nurses who had enrolled in the US Cadet Nurse Corps graduated during the course of the war which helped to address the severe shortage of nurses both at home and abroad. At the time of writing, cadet nurses are the only uniformed corps members to serve in WWII who have not yet been recognized as war veterans by the US Congress.

In their new civilian and military roles, the Rosie the Riveters showed American society that they were as capable as men to work outside the home. For several years, the urgent need for women in the labor market forced socio-economic and political elites to rethink preconceived ideas about gender, stereotypes and the roles assigned to men and women by traditional society. Yet when men returned home after WWII, women’s crucial participation during the war years was swept under the carpet and they were once again relegated to a purely domestic role.

Post created by Pedro J. Oiarzabal. Oiarzabal is the principal investigator of the research project ‘Fighting Basques: Memory of World War II’ (https://www.fightingbasques.net/en-us/) alongside Guillermo Tabernilla. The project is led by the Basque non-profit historical association Sancho de Beurko under the auspices of the North American Basque Organizations. This article is based on research from the ‘Fighting Basques’ project. Oiarzabal holds a PhD in Political Science-Basque Studies from the University of Nevada, Reno. He is the Director of Social Innovation Research at Arima Social Lab (https://oiarzabal.academia.edu/). He can also be found on Twitter as @Oiarzabal.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.